SO CLEAR AND SO COOL

page 2

back to

On Exhibit

SO CLEAR AND SO COOL

SO CLEAR AND SO COOL

page 2

back to

On Exhibit

SO CLEAR AND SO COOL

SO CLEAR AND SO COOL

page 2

back to

On Exhibit

SO CLEAR AND SO COOL

SO CLEAR AND SO COOL

page 2

back to

On Exhibit

|

|

|

|

It has been four years since our last exhibition of paintings by Zhu Qizhan and ten years since his passing. During that time, we have reflected on the many paintings that have passed through our hands. Interestingly, we find ourselves still making discoveries about the man and his work. As a result, we have decided to organize another exhibition. This time, however, we have arranged an on-line catalogue of the paintings in our exhibition that is easily accessible on our website. If you would like to make a purchase, please contact us by email or by phone: (212) 588-1198. We accept Visa, Master Charge, American Express, and Discover cards. | ||

In the final two years of his life, Zhu Qizhan was fortunate to witness worldwide appreciation for his life-long devotion to art, something that often comes too late for many artists to enjoy. There were solo exhibitions at the Hong Kong Museum of Art, the British Museum, and the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco. Indeed, he was present in May of 1995 for the ultimate tribute to him from the Chinese government, the opening of the Zhu Qizhan Museum of Art in Shanghai. |

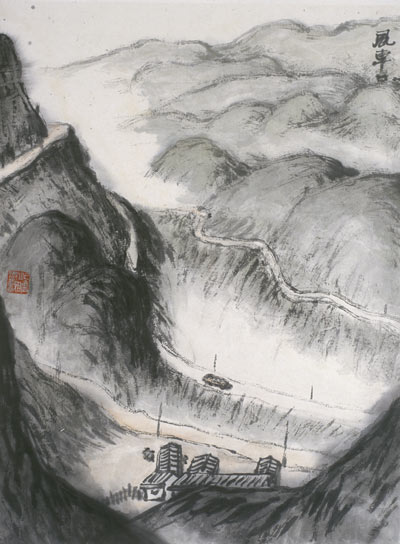

1. Shanghai Countryside.

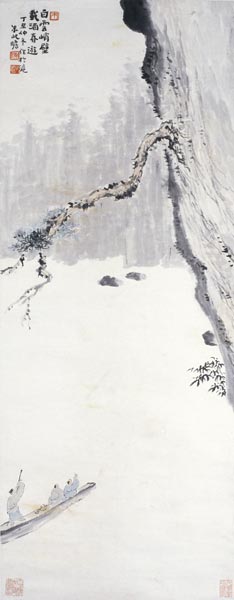

2. Boat Trip. |

|

|

Born in 1892 into a wealthy merchant family with a fine collection of Chinese painting in Taicang, Jiangsu province, Zhu Qizhan received a traditional education. He studied literature, painting and calligraphy as a child and in 1912 entered the Shanghai Art Academy. He was a serious student of art whose rigorous pursuit of excellence resulted in his appointment as a professor in the Shanghai Art Academy in 1913. An early search for a uniquely personal style led him to study in Japan in 1917 where he developed an interest in oil painting. He was back in China for the May Fourth Movement of 1919, which played a seminal role in the development of the artistic paths of many modern artists, Zhu Qizhan included. Under its influence, he left behind the literati intellectual style grounded in Confucianism and ancestor worship, and founded his work on the more basic expressions of artists who arose from the common people, like Qi Baishi. The colophons on his paintings were written in the vernacular rather than the classical mode. His subjects were simple landscapes and still lives, avoiding the painstaking complexity of a formal era. Infused with the Western ideas he was exposed to in Japan, Zhu sought to combine them with the new artistic developments emerging from China’s burgeoning nationalistic identity. Zhu, always a pragmatic man, sought neither to turn back the clock, nor to test the artistic tolerances of his day, but recognized that the use of brush, ink, and paper provided enough room for creative explorations and liberation of his spiritual self. In studying Western oil painting, Zhu responded instinctively to the strong, sensuous use of color evident in the works of post-impressionist artists such as Cézanne, van Gogh and Matisse. At an early age, Zhu recognized that art was a universal language, cutting across cultural and political barriers, and existing at a level of consciousness where it could be used to challenge he complacency of one’s own art, or drawn from, selecting the best elements of another artistic tradition to incorporate into one’s own. | ||

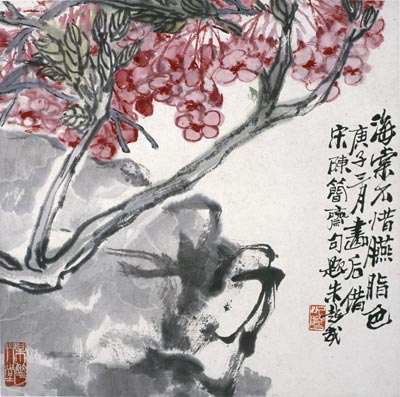

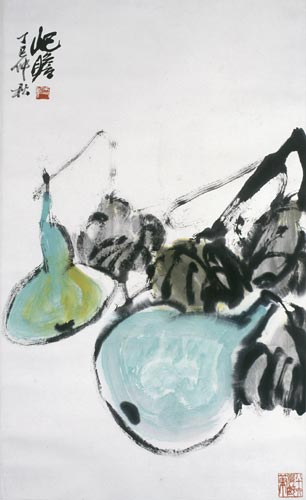

3. Autumn Gourds. Hanging scroll. Ink and color on paper. 32 ˝ x 19 ˝ in. Signed Qizhan. Dated: Autumn 1977. $8,500. |

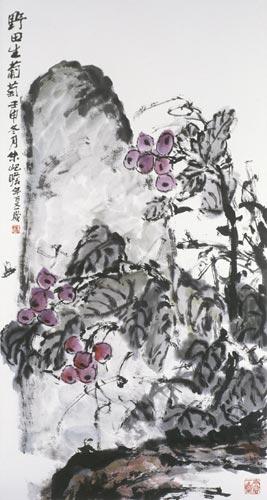

4. Grapes. Framed. Ink and color on paper. 35 ľ x 19 in. Signed Zhu Qizhan at 101. Dated: Winter 1992. Translation: Grapes in the wild field. $12,500. |

5. Amaranthus. Framed. Ink and color on paper. 35 ˝ x 19 in. Signed Zhu Qizhan. Dated Autumn 1984. $8,500. |

| Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Zhu traveled and participated in a number of major art exhibitions, and developed friendships with many famous artists. When the Japanese invaded China, he was in Shanghai where he remained throughout the war. Zhu, who inherited a family soy sauce factory, was dependent upon it for an income but, relying on a manager, never visited the factory. This allowed him considerable time to spend with his artistic friends in Shanghai. They never took part in politics, preferring to paint among themselves. Post 1949, after reunifying intellectuals in their areas of specialty, which for artists meant returning them to their posts at the art academies, he government ordained that Chinese painting should show a new flavor, distinguishing it from the past and reflecting the new society. Based on Mao’s 1942 Yenan Forum on Art and Literature, it was part of the effort to present the one-class concept of the New China and to make art serve the State and serve the people. Traditional painting styles were discouraged and the old artists pressured to leave their studios to paint the lives of the ordinary Chinese. This had to be a difficult adjustment for Zhu who, like most intellectuals, came from a privileged background that could be considered anti-revolutionary. Zhu attended lectures at the Shanghai Art Academy designed to correct his thinking about his background and the narrow life he had been privileged to live. Fortunately for Zhu, his chosen style, though profound, was not elaborate, and his subjects were common objects that were not taken to be anti-revolutionary, so he was able to pursue his style within the context of revolutionary dictates. | ||

|

The Shanghai Painting Academy also sponsored artists on trips to factories and fields to paint the workers as they were performing their tasks. Joining together with other artists such as Xie Zhiguang, Cheng Shifa, Tang Yun, Qian Shoutie, and He Tianjian, Zhu established a sense of solidarity with the masses. Zhu, like others, walked an extremely tight rope to avoid being criticized, because criticism meant dismissal from their positions at the Art Academy. Nevertheless, Zhu Qizhan was very enthusiastic about this new movement in art that he believed would inspire a modern method and would breathe fresh vitality into traditional painting. He hoped that an invigorated Chinese painting style would evolve under the influence of “plein air” sketching, because he was convinced that Chinese painting must continue to evolve. Zhu had little trouble balancing his reliance on traditional painting techniques and his knowledge of Western artists and their techniques. Complementing a life deeply influenced by traditional values with thoughts that remained current and ideas that were ahead of his time, his own requirements for painting were always changing. After years of establishing himself as an artist with a unique style, fulfilling individual goals and his own artistic proclivity, Zhu found himself as part of a team, using his skills to paint New China as a piece of a larger project. Zhu left Shanghai many times to paint the lives of the people and to find ways of improving his paintings. Dating from this period and continuing throughout his career, he garnered inspiration from all things in his surroundings, from reading the news to watching television to eating a plate of crabs. He would keep trying and adjusting new combinations to test out subjects or materials until he got a result that was successful and right for him. He once said to his son, “Painting is difficult; painting something good is even more difficult. Painting is all about using your own style, and selecting the good advice of others. Pick out a road, and travel it all the way.” Zhu’s own style of painting, his early foundation in the techniques of Chinese brush painting together with his knowledge of the techniques and ideas of western painting, was perfectly suited to the new movement in art. Thus it was that Zhu Qizhan created a great revolution in modern painting. He did not set out to do this; he was not the sort of man who starts the ball rolling. Yet, it was within him that the process of reform reached successful maturity. Zhu was the culmination of the exploration, beginning with Wu Changshuo and continuing through Qi Baishi, to paint with radiance and brilliance, to invigorate and transform Chinese painting. Indeed, Zhu did form friendships with the most important artists of the 20th century, with Huang Binhong, Qi Baishi, Pan Tianshou, Xu Beihong, Qian Shoutie, Xie Zhiguang, Xie Zhiliu, Lu Yanshao, and a particularly treasured friendship with Tang Yun. Handsome, with his white beard, smooth skin (a sign of long life to the Chinese) and twinkling eyes, Zhu’s magnetism was immediate, his warmth genuine, and his integrity greatly admired. At his painting table he was Zhu Lao, Grand Master, painting with deliberate and measured strokes, filling the paper with ink and color in perfect balance, his brush eloquent and unafraid. He did not seek to impress anyone with his work, but all who spent time with him left his studio in awe of some intrinsic power that he held quietly within. Historically, the community of artists and intellectuals in Shanghai was always a strong one. Before the Cultural Revolution, there was a “Culture Club” in Shanghai. During every weekend, all the artists of the “Culture Club” would kneel together to cooperate on a massive painting. Zhu attended this exercise regularly. His main reason was to observe people and their paintings and their painting styles. Thus he could compare his paintings with the paintings of other artists, for no matter how great his age, he felt the need to keep pace with the times. Certainly, Zhu’s old age landscape painting marked the maturity of the painting reform. In commemoration of the fifth anniversary of the death of Zhu Qizhan, the Shanghai City Government, the Shanghai Museum of Art, the Zhu Qizhan Museum, and the Zhu family went to considerable effort to arrange a two-week exhibition at the Zhu Qizhan Museum of Art, which opened with a large celebration and banquet on April 22nd, 2001. The paintings in the exhibition were published by the Shanghai Museum of Art in a book entitled Treasured Collection of Zhu Qizhan’s Paintings with an introduction by Cheng Shifa. The exhibition was unique for China in that the Museum cooperated with international collectors to gather a group of paintings that would celebrate the range and depth of the work of this great artist. Also, for the first time, Zhu Qizhan’s collection of sixty seals carved for him by Qi Baishi on stones that he selected was exhibited publicly. So Clear and So Cool introduces fifteen works spanning the years from 1937 to 1992, painted by Zhu Qizhan from the age of forty-six to the age of one hundred and one. Master Zhu’s long career as an artist was characterized by the art of simplification and reduction in the detail as a means of clarifying reality, saying a great deal with a minimum use of brush. He painted with a radiance and brilliance that invigorated and transformed all his subject matter. Despite his quiet and kind manner, Zhu created a great revolution in modern Chinese painting. His fertile and ineffable imagination bridged East and West, past and present, and connoisseur and creator. Throughout his life, he stimulated interest in art among artists and encouraged continual challenge and development in the artistic tradition in order to ensure the continuing vitality of Chinese painting for the future. |

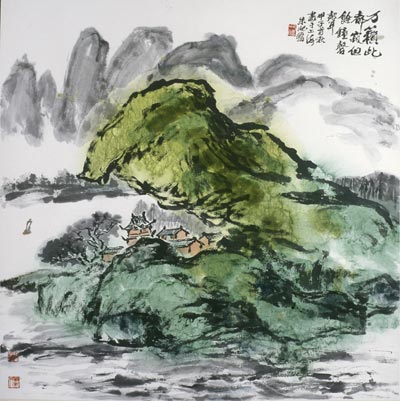

6. Summer Landscape. Hanging scroll. Ink and color on paper. 27 x 27 in. Signed Zhu Qizhan. Dated: Summer 1984. Translation: The sound of the clock’s gong in pure silence. Painted in Shanghai at the beginning of autumn 1984. $22,500.

|

© 2006 Copyright for China 2000 Fine Art